Overview of Interviewing

by William S. Frank, President/CEO of CareerLab®

“It’s not the will to win that matters – everyone has that. It’s the will to prepare to win that matters.” ~Paul W. Bryant (“Bear Bryant”)

Advice on interviewing could fill a book. In fact, I just Googled “books on job interviews” and got “About 378,000,000 results (0.95 seconds)” Of course, there aren’t 378 million books, some of those results are off. But let’s admit it: there’s a ton of information out there on interviewing. LinkedIn and many job posting sites offer advice. The problem is, too much advice, too much contradictory advice, and too much complexity.

Let’s try to keep it simple.

Interviewing is important and must be taken seriously, but the fact is, you are who you are, and you belong where you belong.

Try to be your authentic self. Mother was right: “just be yourself.” When my mother told me that, I didn’t know what she meant. I wondered, “How do I be myself?”

I think we’re authentic when we’re just truthful. Yes, it’s important to be poised and answer interview questions strategically. But don’t bend yourself into pretending you like what you dislike and have skills, ideas, or traits you don’t. That’s a recipe for tragic unhappiness.

If an interviewer asked me, “Do you like public speaking?” I might say, “I’m great at it, the audiences love it, I score ten out of ten on evaluations, but I don’t like it. When I give a speech, everyone loves it but me. I’m nervous months before hand, I overprepare, keep changing my slide deck, and practice too much. When I step on stage, I’m poised and it flows seamlessly. I’m at ease and throw in a few laughs along the way. But when I walk off the stage, I’m exhausted, not exhilarated. Speaking isn’t my greatest gift—writing is. I can think and write beautifully, and that’s what most excites me about this job: the chance to put your company story into words. In that realm, I’m the best there is.”

Reading this you might think, “Gosh, being this honest could rule you out.” That’s true, it might. However, if I’m true to my likes and dislikes, and public speaking is a clear dislike, I don’t want to accept a position only to learn that 15% of my time will be spent pitching large audiences.

As your authentic self, the one-of-a-kind person you are, you’ll be on solid ground. Everyone on an interview panel will realize there’s a deep truth about you, and that creates trust, which leads to job offers.

If you’ve done the earlier planning, resume, and friend letter exercises, you’ll be prepared to interview. Because you’ll know who you are, what you want, and what you stand for. You’ll know your greatest gifts (competencies) and be able to talk to them, because you’ve put words to them in your homework.

By now you know I believe you should feel at home in your new surroundings, not put on the defensive, not demeaned or marginalized. If you’re in the right place, the process will feel right. Things will click. You’ll like the team; the team will like you. Sure, there may be one or two people you don’t mesh with: that’s normal. But you should feel, “This is where I fit.”

When it’s right, your interviewers are prepared. They’ve done a lot of work on your background and know your resume. The interviewer doesn’t open with a question like, “So where did you go to school?”

They care about you because you’re going to be the missing piece to their puzzle, not just another replaceable candidate, one of dozens or hundreds.

So you want to avoid the “stress interview” or “ambush interview” that’s set up to make you fail. It’s a sadistic approach, and I personally would walk away from it. Academics are particularly adept at filling a room with 12-20 interviewers and grilling fearful candidates mercilessly and unnecessarily, often repeatedly. They consider it fun.

Wherever you are, don’t let yourself be treated poorly. It’s bad for your self-esteem, will drag down your performance, and derail your career.

I’ve learned that, “They never treat you better than when they’re trying to hire you.” If a prospective employer doesn’t return calls, texts, or emails, if they are late or don’t show up, if they break promises, or are just plain rude, be advised to walk away. Repeat: “They never treat you better than when they’re trying to hire you.” If they treat you badly during the hiring process, it will only get worse once you’re onboard. Much worse.

Be at ease because, while they’re screening you, you’re screening them. You’re measuring everything that happens by the standards in your blueprint. Are the people friendly, genuinely happy, or fake-happy? One of my executive coaching clients said, “We only hire nice people.”

As a result, Pinnacol Assurance is one of the nicest companies I’ve consulted to. It was number 350 out of 357 corporate clients. Walking the hallway, people actually stopped to say hello, even though they didn’t know me. There were constant little courtesies I hadn’t seen elsewhere.

Under Barbara Brannen’s leadership as Vice President of Human Resources, the company was recognized as a top workplace by The Denver Post for a fifth consecutive year—but the employees also voted Pinnacol the #1 top workplace in 2021. This incredible feat is a testament to their strong culture of caring, community philanthropy, employees and leadership.

Not every company can be a Pinnacol, but they’re out there. And you should aspire to find an organization that cares about its people and cares about you.

As a word of caution, avoid the “Big Company, Big Title, Big Salary” trap. Instinctively, we want to go big, to have a brand name company on our resume, perhaps a Fortune 500 or Fortune 50 to brag about. If “big company” is spelled out in your blueprint, that would be normal.

But big doesn’t necessarily mean best, or happiest.

Take the case of Randy Fuller (a pseudonym). I began work with Randy in 1990 when he wanted to leave the world’s largest oil & gas service company. We partnered on his career through three upward moves, until he became Vice President of Information Technology for a Fortune 350 organization. Big Company. Big Title. Big Salary.

What could go wrong? Turns out, everything.

On his first day at headquarters, the Vice Chairman stepped into his office and said, “Now Randy, you better be watching your back. People will be out to get you.”

We know that IT is often at war with the operating leaders: they want more done than is humanly possible. But this was worse.

Randy described the corporate culture as “Fear—Greed—and Fear.” The senior leadership motivated the workforce by fear. Everyone in middle and lower levels were always afraid of losing their jobs. It was a strategy. Second, senior leaders were greedy for themselves at the expense of lower levels. There was more fear in the threat of ongoing reorganizations and layoffs.

This culture was opposite of Randy’s philosophy. He was a collaborator and team builder. In fact, he trademarked his brand statement: “Success is a team sport.”

Randy knew immediately that he’d made a terrible mistake, yet he couldn’t quit. If he resigned, he’d have to return the $75,000 relocation bonus he received. We talked often and I worried about Randy’s health. After six months, I thought the stress of the job might kill him. Near the end of the first year, the company offered senior leaders a $1.5 million retention bonus (in 2022 dollars) and Randy declined the offer and resigned. It was that painful.

After some punishing detours in his career, Randy accepted a consulting assignment for a global firm where he was based in Paris. I treasure my photo of Randy in front of the Eiffel Tower.

If you’re planning properly, you may spend three or four hours, or more, for an important interview. You have your career blueprint and accomplishment-oriented resume at hand.

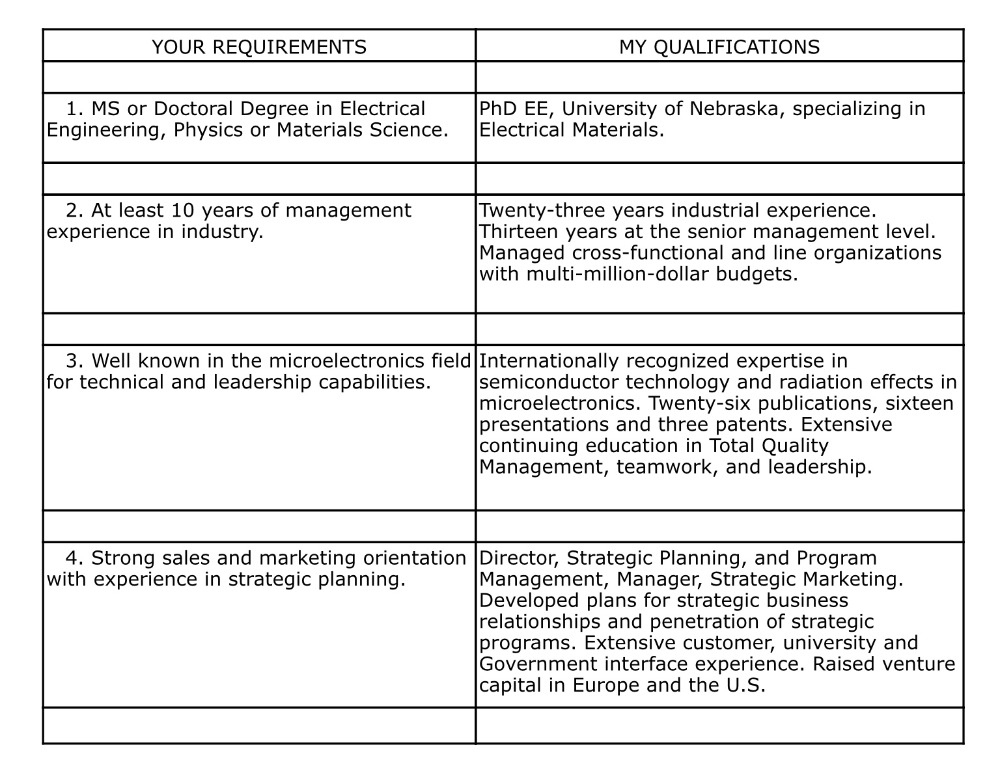

You’ve researched the company inside-out and upside down through the media (LinkedIn, Google, company website, etc.). You walk in armed to the teeth with preparation. You’ve created a chart showing how you fit every requirement you’ve seen. Something like this:

Besides this chart, you know your “value proposition.” That’s the three things the interviewers must know to consider your candidacy.

Let’s face it: many interviewers are beginners seldom, if ever, involved in hiring. An interviewer might talk for 45 minutes, and then say, “Oh, yes. Why are we here? That’s right, to learn about you.”

At that point, you say, “Patrice, here are three things I think you need to know: then you list them. Very simple. Very powerful.

It’s important to know who’s in the room. As the interview is set up, you ask, “Who will I be speaking with?” And you ask for names and titles. If it’s unclear, ask “Who might be on the Zoom call?” And then you research each and every person in great detail. If you know them, even arms-length, they’re friends, not strangers. That’s a big difference.

I wanted to provide outplacement for US West, one of the regional Bell operating companies, a big deal at the time. I invited the Vice President of Human Resources to lunch, and we met at her country club. As is my style, I listened 80% and talked 20%. I’m really curious about peoples’ lives and worldview. Halfway through lunch I said, “Now, Carolyn, you’re really starting to sound like a social worker.”

She jumped in her chair and shouted, “HOW DID YOU KNOW THAT?” I told her, “I read your bio on the US West website.” We had a huge laugh about that, and I told her that I admired her social worker, doing-good background.

Two weeks later she hired me to provide outplacement to a US West senior executive.

In 2011 when Bill Ritter, Jr., left office as Governor of Colorado, his staff hired me to give a career transition class to his executive team. There were about 12 in the room, and I printed and studied, and marked up each and every person’s bio on LinkedIn. In the class, as folks were introducing themselves, I could say something that hit home.

After one woman spoke, I asked, “What does it feel like to be the person who awarded the single biggest grant in the Gates Foundation history?”

Looking shocked, she blurted, “HOW DID YOU KNOW THAT?” I said, “I read it on your LinkedIn profile.

I’m not suggesting you try to be clever with people’s personal details. I am suggesting that it’s vital to know the backgrounds of your interviewers. If you’re in a panel interview, look at and talk to everyone in the room or on the call. It’s the quiet one in the corner who doesn’t say anything during the interview who later tells colleagues, “I didn’t like him; he didn’t see me or speak to me. Thumbs down.”

When I find a quiet one, I often interject, “Kevin, we haven’t heard from you. What are you thinking as we’re talking?” Trust me, they’re always thinking something.

It’s also vital to know how long an interview will last. Some last 20 minutes, others 12 one-hour sessions over two days. “How much time do we have?” has saved me many times.

We showed up on the doorstep of a national consultancy ready to present our offerings to the Vice President of Human Resources. When we arrived, we were told that the VP wasn’t around and that one of her direct reports would meet with us.

I thought: “Red Flag. This person wasn’t planning to meet with us, he’s being pulled away from important projects, and doesn’t want to be here. Probably resents the interruption.”

Knowing that, when the executive walked in, we introduced ourselves and I said, “I know you hadn’t planned this meeting, so here’s what’s going to happen. We’re going to spend the next 15 minutes or so finding a convenient time to meet with the Vice President, and at 1:15 we’re going to be snapping our briefcases closed and walking out the door. Is that okay with you?

The executive was pleased that we’d recognized his predicament. We didn’t foolishly try to sell something to someone who didn’t care. We let him off the hook and gave ourselves a second chance. (Full disclosure: we never got an assignment from the company, but the lesson was well-learned. And we don’t carry briefcases these days, we tote backpacks.)

In any interview you’re likely to have a monkey wrench question, the one that comes from left field and catches you totally off guard. That’s normal. Answer as best you can and move on.

Early in my career I was interviewing to be an outplacement consultant for a regional firm. It was going fine, until one of the owners asked, “What would your enemies say about you?” I stumbled a bit and finally said, “I’m not aware I have any enemies.”

I was young in my career and hadn’t had time to set fires or burn bridges. I was naïve. I think the interviewer was trying to smoke out my weaknesses, and he could have said, “Tell me about a time when you had a conflict with a friend or co-worker.” All humans have conflicts, starting in kindergarten.

Even if you have monkey wrench questions, or feel the job is way off target, go for the job offer. It sounds odd when I say that, because I’m usually talking good fit, but getting an offer is a good thing. As one Vice President of Finance told me, “You can’t decline an offer you don’t have.”

Get an offer. In the quiet of your study, run the offer through your blueprint, and if it doesn’t fit, decline the offer.

Last of all, be patient. One client described his career transition as “the highest highs and the lowest lows.” Certainly, those highs and lows can appear when you’re developing job leads and interviewing. One day you receive a call and are elated. The next day you receive a call and you’re despondent.

That evens out, though, and the highs prevail if you’re “overmarketing,” that is doing more than you need to do to keep the phone ringing. You’re constantly renewing and expanding friendships. As my mentor, Joe Sabah, taught me: “Forget about your incoming mail; focus on your outgoing mail.” Continue reaching out, and as more opportunities develop into warm leads, disappointments still hurt, but they don’t seem fatal.

Companies can be horribly slow to act, to make decisions, and to explain status. Here’s a real-world example:

Donn Lobdell was Vice President of Research and Development for COBE Labs, a pioneer company in artificial kidney, cardiovascular surgery and blood component therapy. Over the nearly 20 years that Donn worked there as a corporate officer COBE grew from $3 million to $400 million in annual sales. They pioneered the first integrated artificial kidney system.

While Donn was there, I sent many engineering candidates to interview with his group. Candidates would have a team interview and then be sent home with a problem to solve, often one central to the business’s success. Two weeks later they’d return for more questions and interviews. They’d be sent home with no clear idea of what would happen next. This often spanned several months. When an offer came from COBE, it really meant something.

Donn left COBE when the company was sold and became my outplacement client. While getting to know him I asked, “What’s the most important part of your job?”

I figured he’d say something like, “artificial intelligence, plastic polymers, or statistical sampling.” Instead, he said, “Hiring is the most important part of my job—because when you’re hiring, you’re creating the future of your company.” That was brilliant, and I’ve never forgotten it.

Let’s remember that the employer’s sense of urgency is different from ours. I went to Lockheed Martin to make a consulting pitch, and asked the Vice President, “When do you need this?” She said, “We need it immediately!” I asked, “What do you mean by immediately,” and she said, “We absolutely must have this in place within the next 12-18 months.” As an entrepreneurial consultant, I thought immediately meant this afternoon by 2:00.

Hiring decisions can be painfully slow with traveling decisionmakers, vacations, holidays, and work emergencies. Give it time. Check in, but not too often.

Once when hiring a consultant for CareerLab®, one of the candidates followed up so enthusiastically and often with everyone in the firm, even sending cards to the office manager, we decided to rule her out. We felt she’d be in our face and too much to handle.

One of my senior executive clients had 17 interviews for a high-level job before finally being turned down. That is a punishing process. Still, she won out by landing the 95-98% good fit in a Fortune 500 company, where she’s worked happily since 2016. She was recently promoted.

Have patience. My Dad, the internist, said the best medicine is often “tincture of time.”

Besides being patient, it helps to be succinct. It might help you to re-read Gary Provost’s article, “Pack Every Work With Power” in the resume section.

My sales approach is understated, soft-sell. I listen 80% and talk 20%, and don’t speak much. But when I talk, I try to say something relevant and powerful. Oftentimes, short is better.

When we were vying for an outplacement program against much bigger, global competitors, I remember tough interviews in the boardroom with the senior leaders. At the end, the decision-maker skeptically asked, “Do you think a small company like yours can handle a large layoff like ours?

Short pause: “Yes.”

“Yes” was my one-word answer, and she gave us the big assignment. I could have relitigated all our staff credentials, accomplishments and firepower, and past client testimonials. I didn’t.

I simply answered her question directly and honestly.

In the 1980s, the savings and loan industry fell into a depression, and brought a lot of the country with it. The first cause was Silverado Savings & Loan, and I approached the Vice President of Human Resources to do their considerable outplacement.

Again, I competed with national firms much bigger and deeper than ours. I presented to the VP and sent her follow-up materials. After ten days I left a follow-up voicemail, but then let her alone to make her decision. A week later she called to give us the assignment. When I asked why, she said she liked us and our programs. She also said, “I hired you because you didn’t bug me like all the other outplacement firms. They were relentless. They called me constantly.”

Now that you’re read this overview, review and study the other articles in the series. As before, print them, mark them up and make notes in the margins. They were written because they’re stories or ideas I’ve told individual clients 1,000 times. They produced results. They bear repeating.

After reading them, please craft your written interview plan (it will differ slightly for each position and company) complete with show-and-tell documents. Walk in armed to the teeth with preparation.

Above all, as you travel the world of work, always remember your one-of-a-kindness.

“The circumstances of your life have uniquely qualified you to make a contribution. And if you don’t make that contribution, no one else can make it.”

~ Harold S. Kushner